02-06-2025

Article

Women, War, and Global Governance: The urgent need for a Gendered Reform of the United Nations

Laura Pamela Aranda Medrano

Introduction: A Global Governance That Continues to Exclude Women

This paper exposes structural inequalities in global governance, focusing on the persistent exclusion of women from leadership roles in the UN and related institutions—despite their vital contributions in crises and conflict zones such as Ukraine. Aligned with the theme “challenging leadership today for change tomorrow,” it calls for a feminist transformation of global institutions, particularly the Security Council, where women—especially from the Global South—remain largely unheard. The goal is not symbolic inclusion but genuine participation that redefines how peace is built and sustained through gender-inclusive reforms and a new vision of leadership and global justice.

1. The Gendered Exclusion in Global Governance

Global institutions like the United Nations were created to promote peace, yet their structures have long marginalized women. Leadership remains predominantly male, reinforcing systemic barriers to women’s participation in global decision-making. As Enloe (2014) notes, this exclusion reflects deep-rooted institutional biases favoring traditional male leadership.

Women’s involvement in peace processes is not only fair but demonstrably effective—agreements are 35% more likely to last over 15 years when women participate (UN Women, 2022). Their inclusion fosters a holistic approach to peacebuilding, prioritizing long-term stability, human rights, and the reconstruction of societies. Still, the UN Security Council and other bodies remain male-dominated, upholding outdated views that security is primarily military, rather than human-centered.

Despite the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda established in 2000 that includes UN resolutions about human rights and UN Women declarations about female and children rights, progress remains slow. Why does structural exclusion persist? What forces continue to silence women, particularly from the Global South? By examining Ukraine and other cases, this paper affirms that inclusive peacebuilding is not optional—it is essential.

2. Women in War: The Ukrainian Case and Beyond

Women have played crucial roles in wartime, taking on responsibilities far beyond combat: organizing humanitarian aid, negotiating ceasefires, and leading local governance in conflict zones. Tickner (2001) emphasizes that women’s contributions challenge the traditional narrative that war and diplomacy are male domains. In Ukraine, this is especially evident. Women have led grassroots resistance, civil evacuations, medical and psychological support, and transnational advocacy. These roles are not auxiliary—they represent crisis leadership. Yet despite their visibility on the ground, women remain largely absent from formal negotiations and high-level diplomacy.

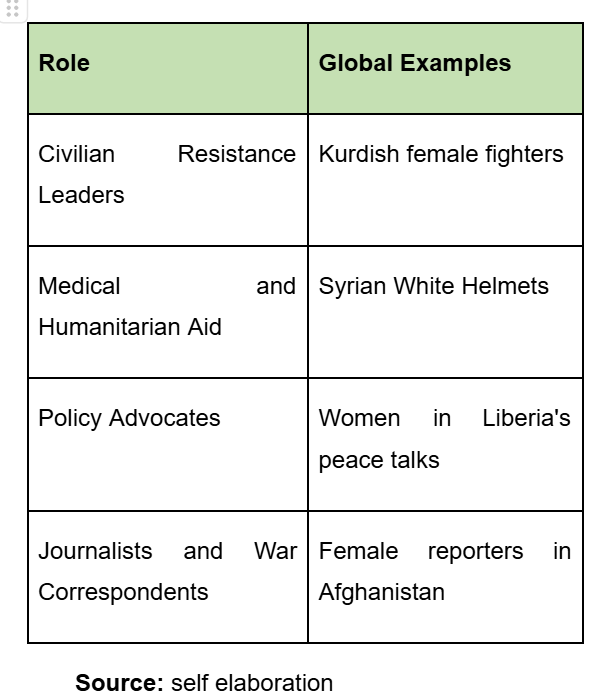

Table 1: Women's Roles in War and Peacebuilding

One of the biggest obstacles preventing women from taking their rightful place in war and peace processes is the deeply entrenched perception of war as a male domain, despite two decades of global discourse on gender inclusion, change remains superficial. Institutions promote rhetorically, but power structures resist transformation. Women in conflict zones often find themselves carrying out critical roles—leading evacuations, negotiating local ceasefires, and providing essential medical care—yet their work is frequently dismissed as “support” rather than leadership. The lack of recognition for these contributions translates into exclusion from high-level decision-making, further perpetuating the cycle of gendered discrimination in international security frameworks.

3. The UN Security Council and Institutionalized Gender Inequality

The UN Security Council, the primary body responsible for maintaining international peace and security, exemplifies how global governance structures reinforce gendered hierarchies. Since its founding in 1945, no woman has ever held the position of UN Secretary-General, and women remain severely underrepresented in high-level diplomacy. Weiss & Daws (2018) argue that "the persistent gender imbalance within UN leadership reflects a broader structural issue, where power continues to be concentrated in male-dominated networks." This underlines the necessity of systemic reforms to break the cycle of exclusion and establish a more equitable global governance framework.

Addressing the Problem of the Veto System

The structural flaws of the UN Security Council’s veto system not only concentrate power among a handful of states but also reinforce a male-dominated leadership framework.

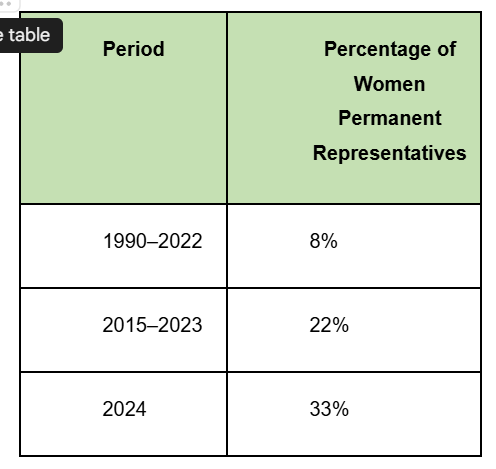

Table 2: Gender Representation in the UN Security Council (1945–2024)

Source: UN Women. (2022). Women at the UN Security Council: a sea change in numbers. Retrieved fromhttps://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2022/10/women-at-the-un-security-council-a-sea-change-in-numbers

Notes:

- Between 1990 and 2022, only 8% of Permanent Representatives at the UN Security Council were women, with more than a third of them appointed in the last four years of that period.

- From 2015 to 2023, the percentage of women Permanent Representatives increased to 22%.

- In 2024, 5 out of 15 Security Council members (33%) had a woman as a Permanent Representative.

This table illustrates the progress in female representation at the UN Security Council over time, showing a significant increase in recent years.

4. Reforming the UN: A Gendered Proposal

To address these systemic inequalities, the UN must undergo structural reforms that integrate a gender perspective in decision-making. This section outlines key proposals to ensure meaningful representation of women in global governance. These recommendations under a gender perspective could also guide international aid to prioritize services and infrastructure that directly impact women-led households, who often bear the brunt of displacement and recovery. Up next, the key recommendations are:

- Gender Quotas in Leadership: Implement a 50% gender parity requirement in UN leadership positions, including the Security Council.

- Women-Led Peace Negotiations: Mandate the inclusion of women in all UN-mediated peace talks, ensuring their voices shape security policies.

- Expansion of Non-Permanent Seats in the UNSC: Allocate seats specifically for underrepresented regions and include gender-balanced delegations.

- Creation of a Permanent Feminist Advisory Body: Establish a feminist advisory committee within the UN to monitor and evaluate policies through a gendered lens.

Beyond leadership and security, the gendered exclusion in global governance has severe economic consequences. When women are excluded from decision-making bodies, economic policies, international aid distribution, and reconstruction programs often fail to consider their needs. Women in post-conflict societies are typically left with the burden of rebuilding communities, yet they receive a fraction of international funds allocated for recovery efforts. According to the World Economic Forum ensuring gender parity within the UN “would not only lead to more equitable policies but also drive economic stability, as research shows that nations with higher levels of gender equality experience faster economic growth and lower poverty rates” (World Economic Forum, 2023). These challenges are further exacerbated by the recent global trend of shrinking aid budgets, which intensifies the competition for resources and often sidelines gender focused recovery efforts. In this context, ensuring gender-sensitive allocation becomes not only a matter of equity but also a strategic imperative for maximizing impact under constrained conditions.

Conclusion: A Future Where Women Shape Global Peace

In a world facing intersecting crises, a feminist approach to UN 2.0 must move beyond aspiration—it must become an imperative for sustainable global governance and peace. Across the world, a generation of women is rising-resisting injustice, challenging power, and refusing silence. Many still face systemic barriers rooted in race, geography, economy, and culture. While some access academic and digital spaces, others remain unheard, invisible, or dismissed. True justice in global governance must center all voices- not just the loudest or most privileged. This article is part of that collective effort: to imagine a future where women lead with courage, where animals and ecosystems are respected, and where justice means inclusion, dignity, and transformation- for everyone, not just a few.

Biography

Laura Pamela Aranda Medrano is a Gen Z Mexican researcher, writer, and activist specializing in geopolitics, global governance, and gender justice. She holds degrees in Law and International Relations, and is currently completing a Master’s in Political Science. She is the founder of LPAM Global Research Lab, an emerging platform dedicated to critical, interdisciplinary analysis of global challenges through feminist and decolonial lenses. Her work advocates for structural reform in international institutions and has been recognized with awards for academic excellence and youth leadership. She regularly participates in national and international forums on peacebuilding, human rights, and sustainable development.

References:

Enloe, C. (2014). Bananas, beaches, and bases: Making feminist sense of international politics. University of California Press.

Tickner, J. A. (2001). Gendering world politics: Issues and approaches in the post-Cold War era. Columbia University Press.

UN Women. (2023). The role of women in conflict resolution: Case studies from Ukraine. Retrieved fromhttps://www.unwomen.org

Weiss, T. G., & Daws, S. (2018). The Oxford handbook on the United Nations. Oxford University Press.